By: Jhanvi Virani

Case File: 54766/230

Immigrants: Michela Coco and Guisseppi Amenta

An Immigrant Victimized by the Land of Immigrants

At the turn of the twentieth century, immigration policy had already begun to consolidate its place as a permanent subset of American legislation. The first major step policymakers made to curtail immigration was the creation of the Asiatic Barred Zone in 1917, which barred immigration of people from the region spanning from Arabia to western Russia. The ban on Asian immigrants, which expanded earlier Chinese exclusion acts, established a clear theme for what immigration policy would be – a tool with which Americans could keep out the individuals who were “undesirable” to them.

In 1920, the majority of individuals seeking entry into the United States were white migrants from Europe, however soon even the status of white European was not enough to keep some from policy discrimination. With the enactment of the Immigration Act of 1917, the number of welcomed immigrants narrowed further with new clauses that increased the head tax required to enter and mandated that all immigrants pass a literacy test before being legally allowed to enter. The new legislation targeted low-income and uneducated European individuals who sought to create better lives for themselves in a new country. It was in this political and cultural climate that Michela Coco arrived at Ellis Island in 1920. Coco was among those impacted by these new rules; she could not read or write, so she could not pass the literacy test and was ordered to be sent back to Italy. However, a clause in the Immigration Act allowed the wives of American residents to enter without passing the literacy test. Since Coco was married to Philadelphia resident Guisseppi Amenta, she pursued her case with legal counsel and requested her deportation to be reconsidered.

Further exploration of this case reveals the lack of trust with which Coco and her word were treated. Before immigration authorities would allow Coco to enter the country, they needed to first prove that her marriage to Amenta was in fact legitimate and not merely fabricated as a ploy to enter and live in the United States. Over the time span of about a month, Coco, Amenta, and multiple witnesses were relentlessly questioned to further explore the details of their marriage. Officers asked Coco very specific questions, like how old she was when she got married, what time of the year was her wedding, and whether her civil ceremony occurred after the church ceremony or vice-versa. Many times, officers were recorded to have asked her the same questions again, hoping her answers would contradict one another, and in some cases they did, but it is unclear as to whether those contradictions can be accredited to lying, emotional stress from the interrogations, or poor memory and record-keeping. Moreover, none of her statements were taken as fact; everything she said had to be cross-checked with her sister and brother-in-law, her husband, and even at times her banker. Though, in the end, Coco was allowed to enter the United States and rejoin her husband in Philadelphia, the nature of the case and how it was handled reveals the hostility with which illiterate immigrants, especially women, were treated in the American immigration system.

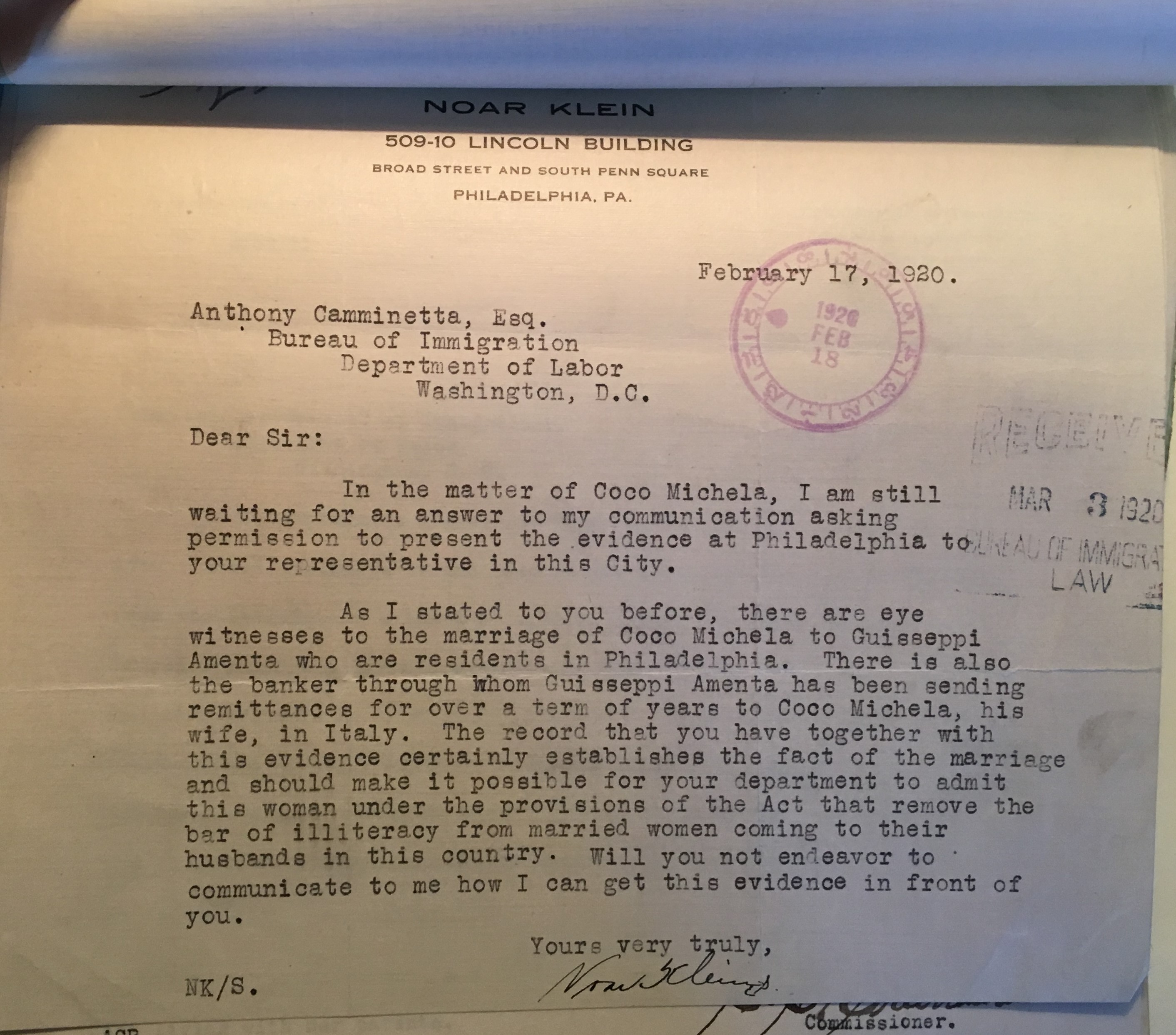

Appealing Deportation

The contents of the document show how Coco’s fate was completely contingent on proving the legitimacy of her marriage. Her legal counsel, Noar Klein, wrote this letter to the Bureau of Immigration because his client was unable to properly prove that she was legitimately married to American resident Guisseppi Amenta, which should effectively waive the literacy requirement created by the Immigration Act of 1917 and allow Coco entry into the United States. He mentions that his client can provide several witnesses to her wedding ceremony, as well as an American banker than can attest to the fact that Amenta sent Coco money on a monthly basis, supporting the idea that their marriage had not been fabricated for the sake of Coco’s entry.

The fact that the letter even had to be written proves that Coco was not given the proper platform to fairly make her case, and even when she was, her word was not trusted. The letter was written as a reaction to a decision that was already made that states that Coco was to be deported back to Italy, but the reality was that she clearly should have been allowed entry due to her marriage to Amenta. However, it is evident that she did not have the means to properly present this information in the past and was now getting the help of legal counsel. Moreover, records of her interrogations prove that Coco was treated with little respect; immigration officers spoke to her like she was someone who’s word could not be trusted without external confirmation. For example, when Coco stated that her husband sent her money for Philadelphia even when she lived in Italy, that information needed to be verified by the bankers who carried out those transactions.

The Misogyny of American Immigration

This case brings up interesting nuances of the dynamics of marriage and gender and, ultimately, how they play into an immigration system built on a patriarchal society. As immigration reform started entering the realm of political discourse in the late nineteenth century, people started falling into two categories– those who could enter the United States and those who could not. The question of what would happen if an American resident married someone would not be able to enter the nation became one the government had to address. Their solution was to allow the husband’s status to carry over to the wife’s, and effectively give men the power to control their wives’ citizenship and residency statuses.

In cases like Coco’s, this policy opened doors to women who normally would not be able to build a life in the United States. However, there also were cases of women who had to give up their American citizenship when they married non-American citizens who did not reside in the United States. Women were downgraded to the status of dependents, and the fate of their residency rested in the hands of their husbands the same way the fate of a child’s residency rested in the hands of their father. The patriarchal ideas with which the legislation was crafted spills over to infect the way with which immigrants are treated in the system.

The issues, stigmas, and discrimination that poison American society go on to reflect the way immigration policy is constructed and conducted; every mistreated migrant becomes a reflection of the consequences of the toxicity of American culture. In order for immigration policy to more accurately reflect American ideals of inclusion, equality, and freedom, it must first trudge past American conventions of bigotry, discrimination, and fear. Is this an idealist aspiration or can the people of this country eventually conquer their instincts to close themselves off to the unfamiliar?