By: Sarju Patel

Case File: 54766/328

Immigrant: George Vik

On February 19, 1920, a Finnish sailor named George Vik arrived in New York from Shanghai on a British cargo ship called the Slavik Prince. Since the ship would depart the country with a Chinese crew, Vik planned to remain in America, substituting his legal status as a sailor with that of an immigrant — an action that was not uncommon for European sailors during this time. As his ship entered the New York Harbor, the imposing main building of Ellis Island foreshadowed the complicated immigration process he was about to face.

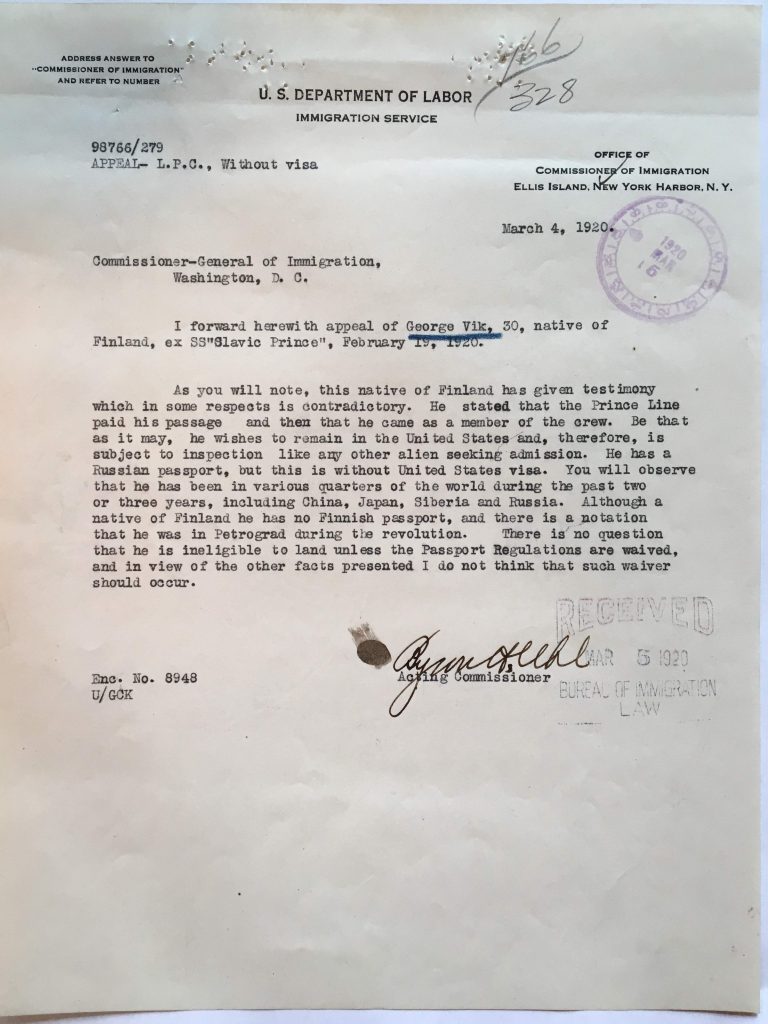

Since he was born in a Northern European country, he was led through a rather cursory and primarily visual medical inspection, and medical inspectors quickly deemed him to be in good health. What turned out to be a more thorough ordeal, however, was the next inspection in which he had to undergo a meeting with a three-person team formed by higher-ranking “keepers of the gate” — the Board of Special Inquiry. After a lengthy interrogation, the Board deemed him “Likely to become a Public Charge” (LPC). This charge was first introduced in the Immigration Act of 1882, which, owing to a subsequent 1891 revision, formally gave officials the right to adjudicate the charge and, thus, debar those deemed LPC. The Board unanimously agreed that Vik displayed the “symptoms” of an LPC: he arrived destitute, had no immediate relatives in the U.S. or anyone legally obliged to assist him, and would have great difficulty in maintaining himself if permitted to live in the United States.

Importantly, those “symptoms” were defined as such by the immigration officials and not by any legislation. As such, the vague LPC charge was, during Vik’s time, continually wielded by nativist officials to justify their own ulterior criteria. What suggested this “alternative” criteria in Vik’s case was the Board’s response to an appeal made by his sister-in-law Eleonora Strom. Strom testified that she would provide Vik with a home, an adequate job, and, if necessary, access to about $1,000. However, the Board swiftly concluded that the LPC charge still stood, suggesting that the officials had some ulterior criteria.

In Vik’s case, this was strongly undergirded by the fear and mistrust symptomatic of the Red Scare. The officials, having meticulously scrutinized his file, were suspicious of his political convictions due to the fact that he had been in Petrograd, Russia, around the time of the Bolshevik Revolution. In any case, Vik was excluded and forced to remain in Ellis Island while the officials tried to find adequate means for deportation.

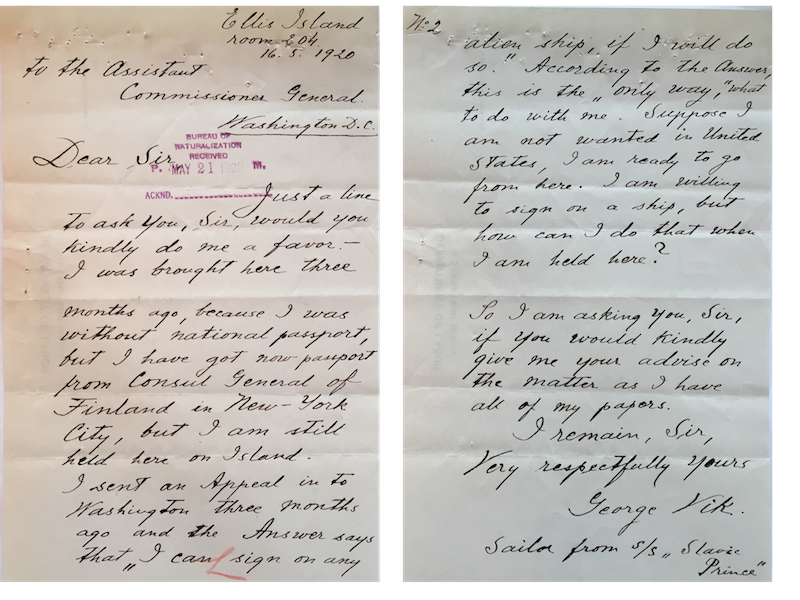

As months drifted by with no response from the officials, he grew increasingly disenchanted about the idea of entering the United States.

And thus, he sent several letters, first beseeching the Assistant Commissioner General of Immigration and, after approximately one month of further wait, the Assistant Secretary of Labor, to help find him a ship. Despite these efforts, he did not get a concrete answer until he contacted an experienced lawyer named Henry Weinberger. Through Weinberger’s efforts, an adequate ship was finally found for him. He boarded the Gothic Prince and left the United States on September 5, 1920 — thus, spending a total of approximately seven months in Ellis Island.

George Vik most probably left Ellis Island frustrated, attributing the officials’ decision to bad fortune. After all, he was only privy to a vague legal basis for his debarment: an LPC charge. As an experienced sailor, who was adept in four languages and had expertise in wire telegraphing, Vik likely thought the charge to be a strange and unreasonable cause for his debarment. His worry was not unfounded, as the reality of his case was much more complicated.

The Insightful Letter

The above letter evinces the complicated nature of Vik’s case. His case, at first glance, perhaps seemed like an easy decision to the immigration officials. As the Acting Commissioner of Immigration at Ellis Island noted, Vik was a bona-fide sailor employed by the “Prince Line.” Moreover, he was a native of Finland — which, being a European country, would typically entail relaxed regulations compared to those arriving from other countries. Thus, as with most Europeans at the time, the officials would have waived “passport regulations” and allowed entry. However, his file presented the officials with what, in the early 1920s, was unquestionable grounds for exclusion: any association with radicalism.

Because Vik’s file placed him in Petrograd “during the revolution,” a place and time strongly linked with radicalism, the officials swiftly deemed him a potential radical.

Thus, what Vik probably considered an innocent trip to Russia, as the letter demonstrates, served as an important basis for his debarment.

The Significance of George Vik’s Case: Indefinite Detention and Travel Bans

George Vik spent approximately seven months in Ellis Island—the bulk of which was spent waiting—bringing to light an enduring issue in immigration proceedings of indefinite detention. A symptom of bureaucratic inefficiency and inadequacy, indefinite detention remains a major issue because immigration law is considered a civil, rather than a criminal, matter. This results in, among other things, comparably fewer resources and, thus, lengthier detentions for deportable immigrants.

George Vik’s case further evinces another enduring trend in immigration policy of excluding immigrants by virtue of their association with countries linked with ideological threats to America. As Vik’s case demonstrates, the officials’ assumption of Vik as a potential radical and, consequently, an undesirable, was only on account of his being in Petrograd during the October Revolution, which helped instate a Communist regime in Russia.

A contemporary manifestation of this sentiment is President Donald Trump’s travel bans: Executive Order 13769 and the slightly “watered down” Executive Order 13780. The countries whose immigration is severely restricted by these orders, President Trump claims, have “significant terrorist presence within their territory.” Thus, all immigrants, he believes, from those countries need be excluded to “protect the security…of the United States”—a position that has, now, been subject to several Supreme Court decisions. Nevertheless, just as Vik was excluded by virtue of his being in a country associated with radicalism, so too immigrants from the excluded countries are, today, deemed undesirable on account of their being in countries associated with terrorism.

Questions for Future Consideration

1) How would the nature of immigration proceedings and their results change if they were deemed criminal, instead of civil, matters?

2) How has engaging issues of national security substantiated President Trump’s immigration policy and, moreover, caused the President (that is, the executive branch) to gain further control over immigration policy, which is typically under congressional authority?

3) How do the experiences of refugees and immigrants who are coming from ideologically undesirable regions compare to those from different parts of the world?

Other Works Cited

Greenway, Ambrose. Cargo Liners: An Illustrated History. Barnsley, Seaforth Publishing, 2011.

Trump, Donald J. “Presidential Proclamation Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry Into the United States by Terrorists or Other Public-Safety Threats.” The White House, Sept. 24, 2017, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/presidential-proclamation-enhancing-vetting-capabilities-processes-detecting-attempted-entry-united-states-terrorists-public-safety-threats/.