By: Nervly Julney

Case File: 53475/377

Immigrants: Jewka Lewkun and Mikolaj Myskow

On August 1, 1912, Jewka Lewkun and Mikolaj Myskow arrived together at Ellis Island from a small town in Austria. Lewkun and Myskow raised concern as they were traveling together despite not being married. Both subjects were held at Ellis Island before The Board of Inspectors interrogated them to investigate the true nature of their relationship.

The questioning took place two days after their arrival on August 3, 1912. The Board of Inspectors first interrogated Myskow with intrusive questions involving Lewkun’s sexual history. Myskow revealed that Lewkun had a child out of wedlock, which raised further suspicion of Lewkun’s morality. However, the immigration officials asked little of Myskow’s relationships or sexual history compared to that of Lewkun.

After the questioning of Myskow, the Board of Inspectors began to interrogate Lewkun. The immigration officials interpreted her sexual reputation as an “immoral woman” enough reason for her debarment. Lewkun later revealed herself as having had a sexual relationship with a man she met through her work in Austria. Lewkun gave birth to a child out of wedlock and before her intended marriage, both her child and partner passed away.

Following both interviews, the Board of Inspectors reached a unanimous decision to deport both subjects for reasons that they were “persons likely to become a public charge.” The Board argued that, based on their economic standing, they would lack the ability to provide for themselves. The Board also believed that they were coming to the United States for an immoral purpose.

After the Board reached its decision, Lewkun and Myskow filed an appeal to the Department of Commerce and Labor in Washington D.C. Four days later, on August 7, 1912, two witnesses appeared on behalf of Lewkun and Myskow to appeal their case. The witnesses explained that they would resume all responsibilities for the subjects until they could provide for themselves. The witnesses also clarified the true nature of Lewkun and Myskow’s relationship. Both subjects merely traveled together because they departed from the same town in Austria together. Despite the evidence immigration officials were presented with, the appeal for both subjects was sustained until Acting Commissioner Uhl agreed to admit them into the country.

The Board of Inspectors were concerned about the morality of both subjects and used the “Likely to become a Public Charge” (LPC) clause to exclude them, using the argument that they would not be able to financially support themselves. However, Lewkun and Myskow both arrived with adequate funds and provided evidence of working American citizens who were willing to support and provide for them on their behalf. Despite having learned the true nature of their relationship and their financial stability, the Board maintained their decision to deport them. The Board of Inspectors believed that if Lewkun entered the country, she would resort to “immoral work” to support herself or would further engage in sexual relationships out of wedlock. The policing of women’s morality served as a method to exclude immigrant women who were believed to be “immoral” who could produce more “undesirable” citizens. It also helped to shape the morality of a paternalistic society in America. By policing women’s morality, immigration officials would ensure that ideals of American society and family would remain intact.

The Appeal

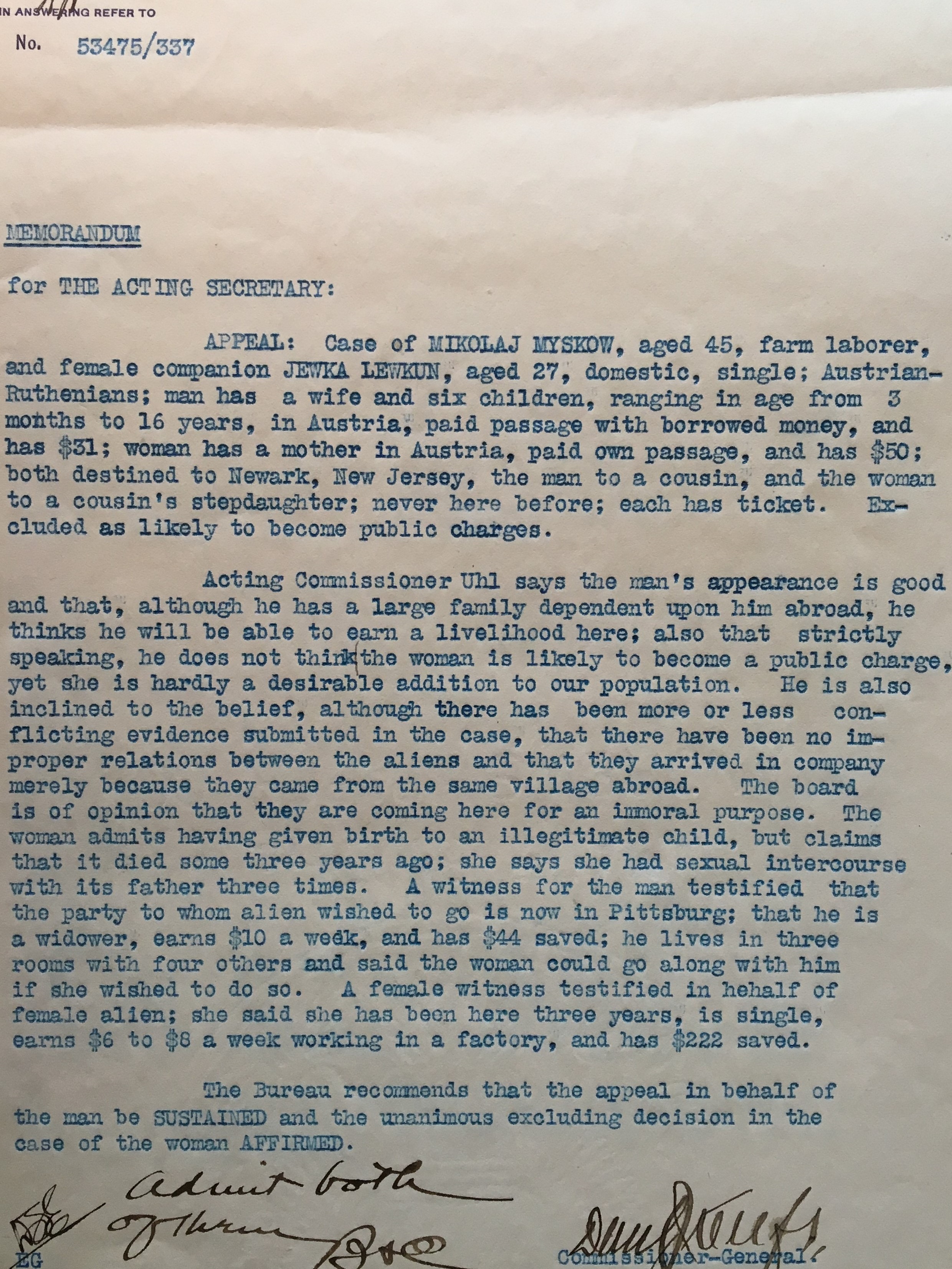

This memorandum was issued to be reviewed by Acting Commissioner Uhl of Ellis Island for the appeal case of Jewka Lewkun and Mikolaj Myskow. There is a brief description of both subjects, detailing their ages, occupational skills, relationship status, and the amount of money they were carrying. The Board of Inspectors decided to deport both subjects on the premise that they would “Likely become a Public Charge.” Both subjects were deemed as having “small sums of money, inadequate to support themselves.” The Board of Inspectors found that their lack of money would lead Lewkun and Myskow to an “immoral purpose.”

Although the Board argued that the two would not be financially secure, the underlying cause for their debarment was based on their morality. Lewkun and Myskow’s morality was being questioned because they were traveling together despite not being married. The LPC clause was used by immigration officials as a means to debar Lewkun and Myskow based on their assumed “immorality” when arguing their ability to support themselves. The statements issued by the immigration officials reveal the subjective gender biases that were implemented against Lewkun as a woman. These statements criticized Lewkun’s morality by emphasizing her sexual history, which ultimately deemed her as deportable.

Later, a brief statement was issued by Acting Commissioner Uhl deciding to admit both subjects into the country. Although Lewkun and Myskow were eventually awarded admittance, this did not occur without invasive questioning and debarment. Even after the true platonic nature of Lewkun and Myskow’s relationship was reported, Lewkun was still criticized. Uhl’s tone was significantly different when appealing the case for Myskow. He was described as having a good appearance signifying that he was able-bodied and “will be able to earn a livelihood.”

Acting Commissioner Uhl states, “He does not think the woman is likely to become a public charge, yet she is hardly a desirable addition to our population.”

The subjective nature of the LPC clause served as a way to reason for deportation of both subjects based on moral turpitude. The memorandum indicates how immigration officials policed immigrant women and their morality, and how an immigrant’s morality was an important factor for their admittance into the United States.

Fear of Producing Undesirables

Lewkun and Myskow’s file illustrates how immigration policies like the “Likely to become a Public Charge” clause was subjective towards women’s morality. Although immigrants as a whole suffered racial and economic biases, policies like the LPC clause allowed immigration officials to scrutinize Lewkun as a woman more than Myskow as a man.

Lewkun’s sexual history was seen as a threat to the American nation’s racial and social reproduction. Since both subjects were traveling together and were not married, immigration officials were also suspicious. The Board of Inspectors feared that Lewkun would further engage in sexual acts outside of marriage, and that she could produce “undesirable” American citizens who would become wards of the state, therefore polluting American society.

The LPC clause served multiple purposes for debarring, detaining, and deporting women. The Board of Inspectors used the subjective nature of the LPC clause and its attributes like immorality involving economic dependency to argue for deportation of Lewkun and Myskow. Immigration officials helped to shape the role of women as second-class citizens in a paternalistic society, but also the woman’s role in the family. The policing of immigrant women’s morality served as a vital tool in preserving and protecting American society.

The concerns that surround immigrant women today still deal with fears of immorality. Issues like sex trafficking and “anchor babies” have been supplemented as another set of exploitative and intrusive standards for immigrant women to avoid in order to be accepted into the United States.

Other Questions

1) How is the status of admittance to the U.S. for asylum-seeking women who may be deemed “immoral” affected?

2) Should there be separate standards for immigrant women and men who wish to become citizens in The United States?

3) Does the sexual history of an immigrant woman threaten the ideals and values of American society?